by Jason Caffrey

photos: Alisa Mackay

“Maybe we need a parent in the room.”

Ben Goldwasser is gently laughing at himself as he describes the creative process he shares with his MGMT partner, Andrew VanWyngarden. “It’s not like we’re totally oblivious when we’re making music. We know when something we’re working on might have more pop appeal or might not. But it’s not something we necessarily have control over. It’s just whatever happens to come out of us at the time.”

The work under discussion is MGMT’s single, In The Afternoon, which dropped in December 2019 as a digital download, with a limited edition 12-inch single released exclusively through MGMT’s online store the following March. It’s a track firmly in the groove of the band’s pop-orientated output, with an eight-minute ambient track, As You Move Through The World, on the B-side. That pairing is a neat summary of the tension that threads its way through MGMT’s output: the commercial work that became gold- and platinum-selling records; and the parallel output of material that is clearly not the product of a hit-factory. In The Afternoon wouldn’t be out of place on a many college students’ playlist, while As You Move Through The World perhaps owes more to Vangelis’ Blade Runner soundtrack than it does to the Billboard charts. And Goldwasser admits that, like a couple of unruly kids, he and VanWyngarden can often produce the opposite of what they set out to. “So we kind of just have to let go”, he says.

In The Afternoon and As You Move Through The World were the first tracks that MGMT produced independently of a major record label. They had been with Columbia and Red Ink (both owned by Sony Music) since 2006. Plenty of musicians would sever a limb for that kind of backing - so why had MGMT decided to go it alone? “In some ways we probably wouldn’t have a career as a band if it weren’t for signing a record deal because, at the time, we weren’t really actively promoting ourselves. We kind of just stumbled into it,” says Goldwasser. “It was a really good break for us early on, and that convinced us that maybe it was worth giving it a go.” MGMT had a generally good relationship with Columbia. “They let us do what we wanted,” Goldwasser remarks. But in the end he and VanWyngarden decided Columbia was no longer a good fit for them. Goldwasser says that sometimes the record company “didn’t really know what to do with us”. So, with a Grammy Award for their Justice Remix of Electric Feel in 2009, plus a slew of other awards from the likes of MTV and NME, MGMT decided it was time to move on.

Long-distance relationship

The way Goldwasser and VanWyngarden collaborate has moved on too. VanWyngarden lives on America’s East Coast, along with the rest of the live touring band, who are all based in the New York City area. Goldwasser though, is in Los Angeles. He takes it turns with VanWyngarden to criss-cross the country, the two of them alternately going to work with the other for a week or so at a time. “I think at first we were a little bit concerned about how we would make it work”, Goldwasser confesses, “but then it just kind of happened and we got used to that way of working.” There had been a hope that exchanging ideas and material remotely would happen more than it has, but mostly, Goldwasser says, “the best things happened when the two of us were in the same room”. There were, nonetheless, happy exceptions, “crucial moments” when some little piece of an idea would make its digital way, coast to coast, across the United States, and “some kind of magic happened,” says Goldwasser. “I remember the song James on Little Dark Age. There was an idea that I had sent. I was doing a lot of stream of consciousness songwriting, where I would just sit at a keyboard and record whatever I did. Every now and then something would come out that was like, ‘Oh, that kind of sounds like a song’.” Goldwasser sent one of those ideas to VanWyngarden and the producer on Little Dark Age, Patrick Wimberly. “They came back with this incredible vocal thing. There was a truth in it that we couldn’t really plan. It was pretty magical. I hope that we write more music like that.”

The partnership between Goldwasser and VanWyngarden began at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, where they were both enrolled as art students. “The University had a really strong experimental music programme,” Goldwasser recalls. “There were a lot of people exploring different genre crossovers. I had a jazz background, and Andrew played in a bunch of bands at high school. We were both raised on a lot of pop music, and we were aware of lots of different kinds of music. In that environment, it didn’t really seem like anything we were doing was out of the ordinary,” he says. “You could just do whatever you wanted.” For their first gig, Goldwasser and Van Wyngarden played a rendition of the Ghostbusters theme song for 20 minutes straight, a performance that concluded with VanWyngarden “riding around on the floor”. The pair then started writing their own material, or at least “something resembling a song” for the next time they performed. That willingness to inject a dose of irreverence into their approach has embedded itself into MGMT’s creative style, which might be described as an organically evolving mix of material, guided by a readiness to let the pieces fall as they will. The pathway that led to a single featuring a naked pop track on the A-side and a too-long-for-radio ambient piece on the B-Side began right there, at Wesleyan. “I think that’s always been the identity of the band,” says Goldwasser. “It just happens that the first thing most people heard from us was an album that had some pop singles on it.”

MGMT’s first album was the platinum-selling Oracular Spectacular, released by Columbia records in 2007. Goldwasser still points to it as a key work: “I think Oracular Spectacular is a great record. And I think it’s a special record to a lot of people - it really means so much to them.” But Goldwasser does not listen back uncritically. “It’s hard for me to listen to it without hearing what I would do differently, or sensing the frustration in something I know I was feeling when it happened. I felt that way about Congratulations too for a while. It was really hard for me to go back to it.” The door to revisiting that album was opened by The Charlatans lead singer Tim Burgess, who featured Congratulations on one of his Twitter listening parties. It was, Goldwasser says, “really amazing” to “experience my own record with fans in real time. There were a couple of moments that I got chills listening to it. I could detach enough from the process and just appreciate the music. There haven’t been too many times when I’ve been able to do that.”

Limited memory

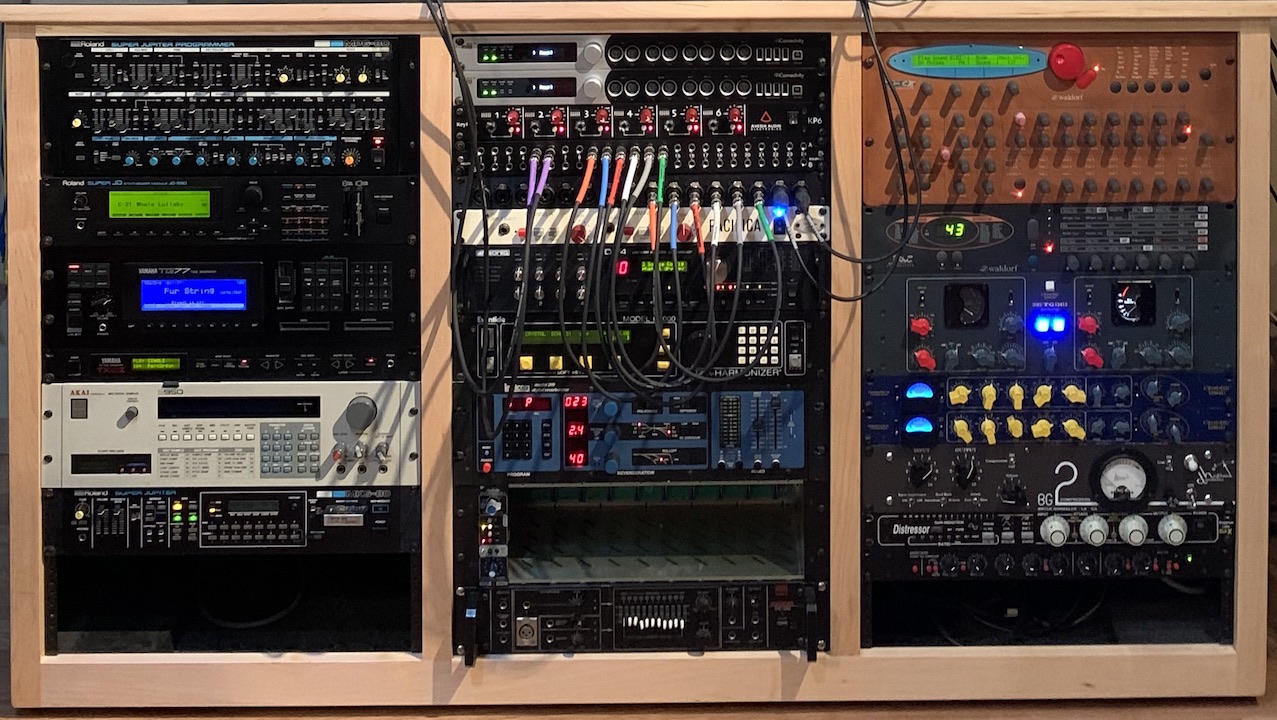

Goldwasser says he is the more technically minded “studio nerd” of MGMT. “I’m more of the keyboard guy,” he ventures. VanWyngard “does the lyrics”, but it transpires he is also a talented drummer. “I don’t think a lot of fans know he plays all of the drums on our records”, says Goldwasser, whose current tech-fetish is rack-mount digital gear from the early to mid 90s. Goldwasser is fascinated by the thought of that kit being the most advanced music-making technology of its time. “It was digital, it was new”, he says, “and nobody had a computer that could load hundreds of plugins. Listening to electronic music from that time, people were making really intricate stuff and getting really creative with sampling with very small amounts of memory. It’s an entirely different set of limitations from what we have now.” In a world where musicians could (and would) buy sample libraries containing hundreds of illegal loops lifted from commercial recordings, and “re-record that or re-sample it”, workflows were a “very organic process”. That’s something that is attractive to Goldwasser, perhaps, in part, because of the frisson attached to flouting intellectual property laws in the pursuit of art. It was “such an exciting time,” he says.

But the limitations of physical gear, and the immediacy that comes with using it - turn a knob, hear the result - are a big part of the draw too. “I’m not one of those people who says that a plugin can never sound as good as analog hardware,” says Goldwasser, “I mean, I can’t tell the difference a lot of the time. But I still love analog hardware for what it does.” One piece of hardware that Goldwasser has enjoyed playing with was Madrona Labs’ Soundplane, an MPE (MIDI Polyphonic Expression) controller with a walnut playing surface, produced in a short run of just 90 units. “It was one of the first of those kinds of instruments that I got really excited about. At the time, I was teaching Max/MSP (a visual programming language for music and multimedia), and one of the things I got really excited about was the space between the notes.” The Soundplane opened up options that weren’t available with other midi controllers, such as, says Goldwasser, controlling a pair of simple oscillators cross-modulating each other, and setting up patterns in between them. “I was like, ‘Oh, wow, you could very easily set up something like that’.”

Reluctant pop star

For all MGMT’s success, Goldwasser rejects the pop-star label. “I acknowledge we’ve had hit records, but at the time we were at the peak of success we really had no idea what that even meant,” he says. “It was so overwhelming that we didn’t have a moment to reflect on what we were doing, or what was happening around us.” Besides which, Goldwasser believes he doesn’t fit the mold. “When I think of a pop star, I think of someone with a certain set of job qualifications - and I don’t have any of them. There was a peak that happened a few years ago, and it was a wild time,” he continues. “What I’m most grateful for is that we’ve had a career that lasted beyond that, and the ability to reflect and grow and build on what we’ve done before. I think a lot of artists who’ve experienced commercial success don’t get that opportunity.”

So did Goldwasser enjoy the “wild time”? It’s tempting, given his reluctance to accept the pop star moniker, to suggest that he’s not entirely cut out for a life of trashing hotel rooms. “I absolutely enjoyed it,” he insists. “Looking back especially on the opportunities to travel and experience so many places. And to just have the experience of getting on stage night after night and playing music. I can’t even comprehend how much growth I got out of that. But there have also been so many times when I’ve been on the road for weeks and just completely exhausted and miserable, thinking ‘Why on Earth am I doing this?’. I think in general I wasn’t designed to be a touring musician, and I’ve been kind of fighting against it for many years.”

That struggle appears to be over for the time being. Goldwasser has settled into a more comfortable rhythm with MGMT, where there is no pressure to figure out the next step for the band. “It feels now like something we can do in our own time, whenever we’re ready,” says Goldwasser, “and I think both of us are excited about the idea of striking out on our own a little bit too, producing other artists or doing soundtracks. Some parts of operating under the traditional framework of a touring rock musician eats up a lot of your time,” he explains, “and makes it really hard to focus on anything extra-curricular.”

Reflecting on MGMT’s journey from that first college performance with VanWyngarden, Goldwasser ponders how he would explain his success to any early-career musician. “I don’t know why it worked, and I can’t say it would work for anybody,” he says. “But I do know that when I see somebody who spent too much time trying to be successful or get attention, even when they did end up with a successful career, a lot of them are miserable. So I’m incredibly thankful to be in the position I’m in right now. And I don’t take it for granted.”