Ripping The Script: clipping.'s Jonathan Snipes Crossfades Between Film Composing And Hip-hop Innovation

by Dave Segal

Along with RZA and DJ Muggs, Jonathan Snipes is the rare music producer who’s straddled the worlds of film composition and hip-hop. Unlike Robert Diggs and Lawrence Muggerud, though, Snipes began his musical career in soundtracks and sound design for theater. (Snipes also did stints with rave unit Captain Ahab and noise group Unnecessary Surgery.) In 2009, Snipes, fellow producer William Hutson, and rapper Daveed Diggs formed clipping., hip-hop’s most interesting iconoclasts.

Clipping. are poised to release their sixth studio album, Dead Channel Sky, on longtime home Sub Pop Records, and it’s another mind-bending mash-up of various electronic styles and lyrical flows. But before we delve into the splendors of clipping., let’s dig into Snipes’ unlikely path to becoming a prolific film scorer and hip-hop form-breaker.

Snipes’ father passed away when his son was 8, leaving behind a large record collection that was heavy on classical music. That music provided the bulk of his childhood’s soundtrack. Because Snipes’ mother shielded him from television and the radio, he would only hear tantalizing bits of non-classical music outside of his house.

As he progressed through his teens, though, Snipes became fascinated with outliers in his dad’s collection. Philip Glass’ 1985 soundtrack for Mishima especially captured his imagination. “That Mishima soundtrack cover—the only Philip Glass [record my father] had—was crazy-looking to me,” Snipes said in a phone interview. “And I’d never heard music that sounded like that, that was that repetitive, that had electric guitars and drum sets mixed in with string quartets and synthesizers.”

Snipes was 11 when he first heard Mishima, and it “was the first in a long litany of records that broke my brain.”

“I had to listen to this over and over again, until I had assimilated it into my language.”

As he entered high school, Snipes had greater freedom to explore music, thanks to his mother loosening control over his listening habits. Nirvana, Nine Inch Nails, and Aphex Twin opened his mind in those days, but it was the GaijinCD4 album by Disc—a collab between Matmos, Lesser, and Kid606—that blew it wide open.

“I bought it because one track was made out of a Michael Nyman piece [“Call It In The Air”].”: GaijinCD4 taught Snipes that

“anything can be music and you can do crazy stuff and it’s really compelling to listen to. You can find musicality in the broken technology around you and the sounds that people don’t want.

“Around that same time, I found MP3.com, rest in peace. That was my first exposure to just anybody making music and uploading it.”

Thus inspired, Snipes began to create his own music on a computer, albeit with the same nonchalance he used with MS Paint or playing Doom. “I never thought I’d be a musician because I lacked the discipline to practice. And the only window into being a real musician that I knew was the Western conservatory. You have to play the same two-minute Mozart piece 12 hours a day if you want to be even passable. I hated that. I love a lot of that music, but I was so bored by practicing. I still am. It’s a huge problem for me.”

At UCLA, Snipes studied theater sound design, and he’s been teaching that discipline at the same university since 2008. He’s worked on over 40 film and TV soundtracks, including Room 237 (2013, with Hutson), Excess Flesh (2016), A Glitch In The Matrix (2021), and Batman Unburied (2024). Some highlights: “Universal Weak Male” flexes muscular, spine-tingling, Patrick Cowley vibes; “Excess Flesh” summons momentous battle action with steely determination; “I’ve Been In Your Head” conjures the foreboding beat science of Scorn and Meat Beat Manifesto; The Nightmare (another Hutson collab) immerses you in dank, pitiless desolation. “Inside The Matrix”—my favorite piece by Snipes—generates 12 minutes of insanity-inducing, Steve Reich-ian hypnosis.

While most of his soundtrack work has come from low-profile horror movies, Snipes can easily shift modes when necessary (see the lush electronic score with soaring choirs and twinkling synths from 2015’s Starry Eyes). “In film, there’s not a lot of projects I turn down,” Snipes says. “I will turn down projects that don’t have enough budget for me to even do the thing they’re asking for. But I find that there’s usually a way to make any project interesting to me.

“I’m not getting a lot of crass, commercial work that isn’t fun. I’ve done a few of those, but I’m getting approached by interesting people pretty much all the time. I have turned down work that would have been really good money, but I saw nothing of interest.”

Did Daniel Lopatin get some of those projects? Snipes laughs and says, “No. He’s done some stuff that I would love to work on. Certainly, I would love to get his budgets. But I’m not there. He has access to a tier of projects and budgets that I don’t seem to be able to crack into. I’d so much rather do one Uncut Gems every two years than three micro-budget horror movies or documentaries a year. Not that I don’t like the projects I work on, but it’s exhausting to be constantly grinding without having quite enough resources.”

His discography clearly shows that Snipes is drawn to horror films. Is it the moods that attract him?

“The reality is, almost everybody starts in horror, because those are the low-budget movies that need original music.”

“And that music can be made pretty cheaply. It also happens to be my taste; I love horror movies. I love horror-movie soundtracks. I understand the world and I do okay at that, so I keep getting [the projects].

“I’ve never scored a Hallmark or Lifetime movie, which is the other place where people start. Except I sort of just did. Because I did Adult Swim’s Yule Log 2, which is like a fake Hallmark movie. It was genuinely really fun.

“That’s something that will always get me to say yes to a project: Oh, I’ve never done that before, but I bet I could. I like assignments and briefs. Which the band clipping. indicates, too. That has rigid constraints and all three of us are really good at following a brief. That’s also what I like about film music.”

Do you find that the methods you use for soundtracks apply to the work you do with clipping., or are you using totally different muscle groups in the band situation?

“A little of both. There is a fair number of clipping. songs that started as score cues. Often what will happen is, I’ll make something that doesn’t quite work for the movie, but it’s an idea that I like. If it doesn’t work because it’s too weird or too harsh or sounds too much like sound design, then I set it aside and play it for Bill and Daveed. ‘Hey, we could loop this differently or put it in a different structure.’ There are a handful of things that started that way. Even with just one sound. More of that happened before, maybe, but rejected score cues get added to the folder of clipping. ideas a lot.

“Clipping. was the project that taught me my interests were compatible and informed each other. Clipping. was the one where if I take all the acoustic ideas that I’ve learned from theater sound design and I apply those conceptual things to making a rap song, that’s interesting. Because even though it’s an obvious connection to me, it’s not a thing that people maybe have heard before would have done.

“Clipping. made a song called ‘Run For Your Life’ where Daveed is rapping over beats in cars that drive by. So he’s rapping over nothing on the street, then a car drives by and he’s perfectly in time with it. I wouldn’t have thought of that if I wasn’t a theater sound designer. Delays and narratives, the way acoustics work and things like that. It’s a very theater idea.”

What distinguishes clipping. is how unusual and shocking the music is compared to that of most hip-hop artists. They have an unusual configuration of two producers and one MC, so it would be illuminating to know how clipping.’s tracks manifest.

“We’re all new dads now, so we’re figuring out how the hell we can make music,” Snipes says. “We also don’t live in the same city. It used to be easy when we all lived in the same neighborhood. We would hang out and music would just kind of happen. But now we have to plan things and that doesn’t seem fun.”

Clipping.’s members have known each other for decades and their musical tastes have evolved communally, enabling them to work with what Snipes calls “a shared language.” During their undergrad days at UCLA, Snipes and Hutson bonded when the former overheard the latter chattering about a Chris Cunningham-directed Squarepusher video. They’ve been inseparable collaborators since.

“Daveed was Bill’s childhood friend from the Bay Area. Daveed was at Brown while we were at UCLA. He’d get out of school earlier and would crash on our couch for a few weeks. Daveed wasn’t a staple in my life till he moved to LA in 2009, 2010. By that point, Bill and I had started doing songs as clipping. that were remixes. Daveed said, ‘What if we did an original song like this?’ And the band came together.

“Before starting anything, Bill and I have a very long conversation. If Bill has an idea, it’s ‘here’s an idea in experimental music. Here’s a kind of rap song. What if we made that rap song with this very experimental-music technique?’ If Daveed has an idea, it’s usually a cadence, a rhythmic idea for the way that the vocals will work. And if I have the idea first, it’s usually aesthetic. I made this sound and I’ve not heard anything like it. Or I made this field recording that I think has an interesting character to it. Usually, my ideas come from the acousmatic/sonic side. Bill’s are usually more like a critical-theory essay about music in general. And Daveed’s are poetic ideas.

“Clipping. songs are always a confluence of a bunch of different ideas. They all sort of coalesce in a place and the synchronicities between them are varying degrees of intentional.

“’Say The Name’ [from 2020’s Visions Of Bodies Being Burned] uses a quote from a Geto Boys song. I always have a list of ideas for a record. Bill wants to make a song that uses that Geto Boys song as a hook, because that’s the scariest line from that song and we’re making a horror record. I want to make a Chicago, Dance Mania-inspired house track about Candyman.

“I was listening to a Wax Master track where he was shouting out different projects near his in Chicago and he shouted out Cabrini Green, which is where the Candyman movie takes place. I thought there’s gotta be a whole litany of Chicago house tracks that sampled Candyman. It’s a horror movie, probably my favorite movie, and again, a Philip Glass score.

“I also have a great love for electro and breakbeat records from the ‘80s that sampled RoboCop. There’s like a million of them.”

“What if there’s this whole Chicago house/Candyman scene like that that I’ve just been unaware of? ”

“But I couldn’t find any, so I said, ‘We need to make THAT. We need to make a Dance Mania track that samples Candyman.’ We didn’t sample Candyman, but the song’s clearly about that movie and the Clive Barker story.”

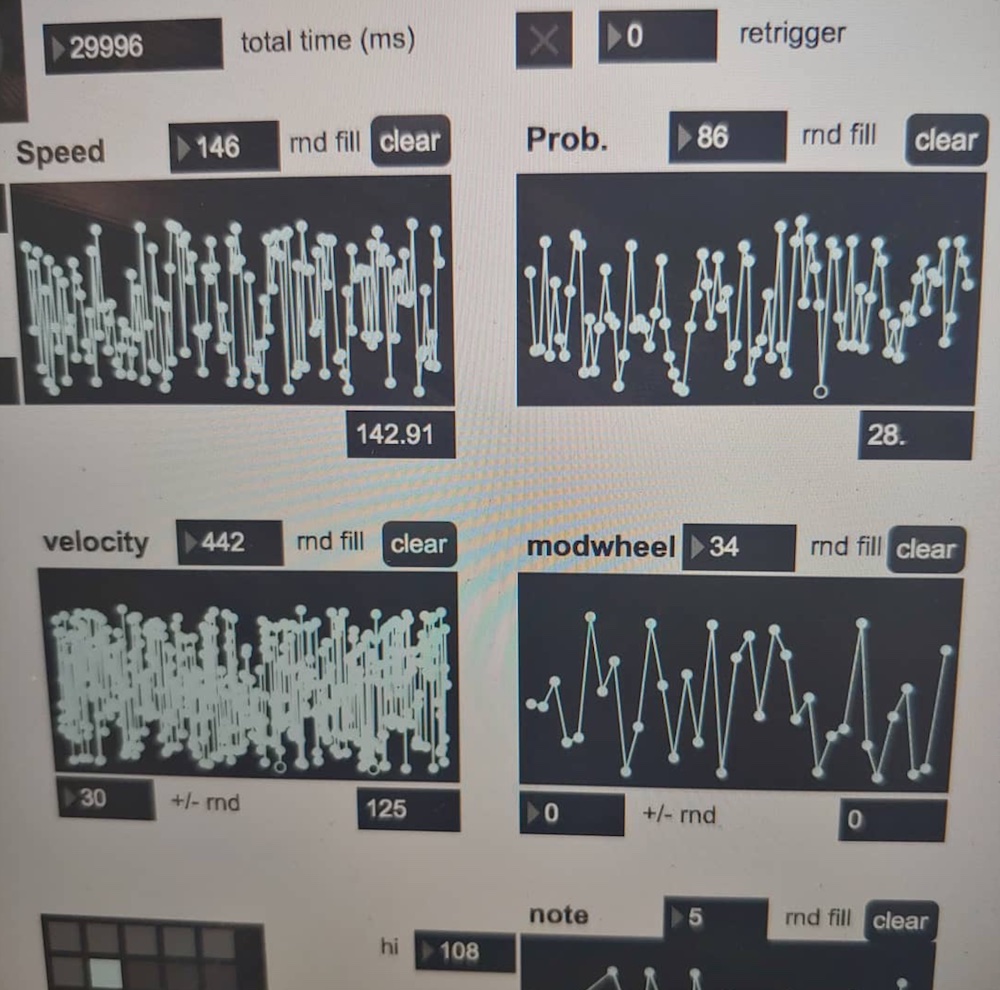

Madrona Labs products figure heavily in Snipes’ studio. He has been a champion of the Seattle company’s products since Aalto emerged in 2009. “I buy everything the moment it’s announced, because they make really interesting sounds that nobody else can do. I know I used Aalto in a demo of our new song ‘Run It,’ but I replaced it with my modular later. I use Aaltoverb live with clipping. because it’s so tweakable. It’s a very playable reverb, in a really fun way.

“I’ve been using Sumu quite a bit in the film work I’ve done since it came out. I don’t think I used it in Yule Log, which would have been the first big project. I used it in another movie I got fired from. But I have been using it a lot in this short film I’ve been scoring. It’s pretty amazing. Sumu truly does things nothing else does in a way that’s really exciting. I’m sure I’ve used Virta; it’s one of my favorite vocoders.”

What is it about Sumu that sets it apart from other gear you’ve used?

“It’s this special combination of an incredibly technical and precise tool that, also, I have no idea what half of it does. Some of it is incredibly intentional, but some of the knobs I just tweak until I get an incredible sound. It represents the way I normally work, which is in an extremely precise and technical way, and the way that I’m trying to allow myself to work, which is free play and fun.

“In undergrad, I did a project for a media class where I used a terrarium filled with sand to make an FFT [Fast Fourier Transform] curve… Like a camera on a terrarium on the sand as a way to literally sculpt sound, like, dig the sound, pile up frequencies. It’s like an EQ curve you physically made out of sand. It didn’t sound good and it wasn’t interesting. That was me learning that any sound could be represented with additive synths, if you had enough partials.

“A sampler that moves fluidly between the wave form and the spectral domain is appealing to me, because of the kind of manipulation you can do. Treating samples as oscillators is cool and unique and not a lot of people have done that. And nobody’s done it in the way that Sumu’s done it.”

Snipes hasn’t used Sumu with clipping. yet, but he plans to. “The funny thing is, I’ve been using it a lot while scoring a UCLA student film. They wanted a section of it to sound hyper-poppy. 100 gecs was one of their references. I was using Sumu to make the more weird, broken, esoteric sounds until I figured out it’s actually an awesome Trance Gate sequencer. You can actually make really clubby stuff in Sumu. So I used it for that stuff.

“When Aalto came out, they said, ‘When you input your serial number, it recompiles the plug-ins so that yours sounds unique.’ I thought, ‘That’s a company I clearly need to be supporting.’”

Snipes’ immediate concern now is preparing for clipping. tours in support of Dead Channel Sky (out March 14), the trio’s most diverse full-length. Inspired by William Gibson and other cyberpunk authors’ dystopian visions, Dead Channel Sky pits Diggs’ amphetamine-fueled bars against a panoply of electronic-music styles—technoise, Cubist house, acidic electro, boom-bap, and on the Nels Cline-aided “Malleus,” a fusion of mad, Squarepusher-esque d&b and guitar antihero Buckethead. The album represents the zenith of the group’s mercurial noise sculptures and disorienting beat programming.

Credit, too, must go to Sub Pop, which gives clipping. complete creative control. “Yeah,” Snipes says,

“we can do whatever we wanna do, as long as it’s not illegal.”

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Clipping's sixth album, Dead Channel Sky, is out March 14, 2025 on Sub Pop Records.